utorak, 5. travnja 2011.

Pan - Greek God

Pan is distinctive among the Greek gods because of his hybrid human-animal form (theriomorphism).

The earliest images of Pan, in bronze sculpture and in a Boiotian vase painting of the early fifth century, show a goat-headed god with a human torso atop a goat’s hind legs.

Originally a guardian of the goats whose character he shares, he achieved Panhellenic status only in the fifth century, when his cult was introduced from Arkadia to Athens and rapidly diffused to the rest of the Greek world.

Many etymologies have been put forward for his name, which is also known in the compound form Aigipan (Goat-Pan). The most convincing makes it a cognate of Latin pastor, so that Pan is “one who grazes the flocks.”In Arkadia itself, Pan’s myth and cult were not standardized.

There were conflicting views of his genealogy, the most common being that he was the son of Zeus and twin of the national hero Arkas, or that he was the son of Hermes and Penelope. His connection with Zeus sprang from their association on Mt. Lykaion, the sacred mountain of the Arkadians.

Pan possessed a sanctuary on the south slopes of Lykaion, where in keeping with his identity as both goat and goatherd, he offered asylum to any animal being pursued by a wolf (lukos). A votive dump excavated here revealed many late Archaic and early Classical bronze figures, cut-out plaques, and terracottas with subjects reminiscent of those at Kato Symi: hunters, men carrying animals for sacrifice, and Hermes. Both youthful and mature males are depicted, and the bronzes include dead foxes, a standard courtship gift presented by adult males to their favorite youths. Inscribed pots show that the sanctuary was sacred to Pan, whose role as a god of the hunt and Master of Animals made him well suited, like Hermes, to sponsor maturation rituals.

Continue reading

utorak, 29. ožujka 2011.

Atlantis - Facts

Plato’s story of Atlantis has the unenviable reputation of being the absurdest lie in all literature. One major problem has been the long eclipse which Plato’s reputation as a philosopher and political thinker suffered during the twentieth century.

Some scholars have written about Plato in such vitriolic terms as to test the boundaries of the term ‘scholarship’. He has been damned for his assumed moral decadence, on the strength of what he wrote in the Symposium, even though he argued for legislation against homosexuality in the Laws; he has been condemned for the obscurity of his cosmology and for his totalitarian politics, his approach to state education sounding uncomfortably like the strategy behind the Hitler Youth.

Some scholars have written about Plato in such vitriolic terms as to test the boundaries of the term ‘scholarship’. He has been damned for his assumed moral decadence, on the strength of what he wrote in the Symposium, even though he argued for legislation against homosexuality in the Laws; he has been condemned for the obscurity of his cosmology and for his totalitarian politics, his approach to state education sounding uncomfortably like the strategy behind the Hitler Youth.

The adoption of the Atlantis allegory by the Nazis seriously damaged Plato’s reputation. Hitler admired Plato’s cyclical view of history involving periodic catastrophes and the return of the demi-gods, discussing it frequently with Hermann Rauschning, who observed, ‘Every German has one foot in Atlantis, where he seeks a better fatherland and a better patrimony. This double nature of the Germans [to live in both real and imaginary worlds] is especially noticeable in Hitler and provides the

key to his magic socialism.’

There is also a parallel, ‘alternative’ twentieth-century literature which has sometimes sought to establish the truth of Plato’s story by refuting what has been learnt through the natural sciences, and that too has alienated academics. Few scholars have been prepared to expose themselves to ridicule from their colleagues by discussing the matter, and it is symptomatic of the climate of opinion in the twentieth century that a young academic who saw a link between the Minoan civilization and Atlantis at the time of Evans’s Knossos excavation felt that he had to publish his ideas anonymously.

The story which has produced such extremes of credulity and incredulity was written down for the first time that we can be certain of between 359 BC, when Plato returned to Athens from Sicily, and 351 BC, when he died at the age of 81.

In a preamble he claimed the story had been handed down to his narrator, Critias, from a distinguished ancestor of Critias, the statesman Solon, who heard it in Egypt in about 590 BC. The Timaeus was written as a sequel to the Republic, and its opening pages show Socrates asking for a narrative to illustrate the ideal state in action.

In a preamble he claimed the story had been handed down to his narrator, Critias, from a distinguished ancestor of Critias, the statesman Solon, who heard it in Egypt in about 590 BC. The Timaeus was written as a sequel to the Republic, and its opening pages show Socrates asking for a narrative to illustrate the ideal state in action.

Critias’ story about the war between Atlantis and the prehistoric Athenians is by no means the main part of the Timaeus, a seventy-five-page discourse on cosmology by the astronomer Timaeus. The discourse throws no light on Atlantis.

At first sight it looks as if Plato realized the usefulness of the story only after completing the Republic, and slipped it into his next dialogue as an after-thought.

It nevertheless reappears in the Critias (113C–121C), and the short account in the Timaeus (23D–25D) is really a trailer for that.

The more detailed Critias breaks off at the moment where Zeus is about to pass judgement on the mortals. Since that moment in the 350s BC, the story of Atlantis has hovered between fable and folk tale, taken as history by some, acknowledged as allegory by others. Today some take it literally, others see it as didactic novella; in the ancient world too opinion was divided. Is the story true? If so, where was Atlantis? The longer version mentions ‘the extremity of the island near the Pillars of Heracles’ and ‘the war between the dwellers beyond the pillars of Heracles [Atlanteans] and all that dwelt within them’. The shorter version is clearer still: ‘in front of the mouth which [Greeks] call the pillars of Heracles, there was an island larger than Libya and Asia together’. Plato is evidently describing an island-continent out in the Atlantic Ocean, just west of the Straits of Gibraltar. There are nevertheless

possibilities other than the obvious one. Although Plato may have placed Atlantis far to the west in an ocean whose immensity was in his time only just being recognized, the original of his story, the Atlantis described by Egyptian priests 250 years earlier, was smaller and nearer to home. The term ‘Atlantic’ is misleading; as late as the first century BC, Diodorus (3. 38) was using it for the Indian Ocean, so it may be wiser to translate it less precisely as ‘outer’ or ‘distant’ ocean.

We cannot assume ancient authors meant the same as us by either ‘pillars of Heracles’ or

‘Atlantic’.

Both place names and geographical perceptions shift with time, and the world of fourth-century Athens was already larger than the world of the Egyptian priests of 600 BC. To the Egyptians, a huge island in the ocean to the west could have been Sicily or even Crete. To the early Greeks the pillars supporting the corners of the vault of heaven might be anywhere remote. Even as late as Strabo’s time opinions differed about the location of the pillars of Heracles; some thought it was the mountains on each side of the Straits of Gibraltar, others argued it was even further west. There was even disagreement about whether the pillars were real pillars, perhaps made of bronze, or mountains. Before the sixth century BC several mountains on the edges of mainland Greece were seen as supports for the sky.

Amongst others, the two southward-pointing headlands on each side of the Gulf of Laconia were pillars of Heracles. Then, to the Greeks, a large island with one end just outside the pillars of Heracles could only have meant Crete. The exotic civilization of Atlantis could then have been the Minoan civilization, which threatened the mainland Greek and Anatolian cultures not 9,000 but 900 years before Solon. Support for a Peloponnesian location for the pillars comes, unexpectedly, from Egypt. The Medinet Habu texts, dating from 1200 BC, describe the Sea Peoples invading from islands to the north (possibly the Aegean) ‘from the pillars of heaven’, by which the Egyptians probably meant that the invaders came from the end of the world as they knew it.

The power that held sway over all the island and over many other islands also was the economic and possibly political power of the Minoan civilization, which was centred in Crete but enmeshed most of the Aegean region and reached out to trade, among other places, with North Africa (‘Libya’) and Italy (‘Tuscany’).

The island of Crete was not swallowed up by the sea, but perhaps the tradition was a misremembering of what happened to the Minoan trading empire, which contracted during the fifteenth century culminating in the fall of the Knossos Labyrinth in 1380 BC. It was as if the invisible network of trading routes and political controls had unk to the bottom of the Aegean, perhaps in the face of competition from Mycenae, metaphorically ‘swallowed up by the sea’.

The island of Crete was not swallowed up by the sea, but perhaps the tradition was a misremembering of what happened to the Minoan trading empire, which contracted during the fifteenth century culminating in the fall of the Knossos Labyrinth in 1380 BC. It was as if the invisible network of trading routes and political controls had unk to the bottom of the Aegean, perhaps in the face of competition from Mycenae, metaphorically ‘swallowed up by the sea’.

The thesis of this articles is that the story is not one piece of identifiable proto

history but several, and that Plato drew them together because he wanted to weave them into a parable that commented on the state of the world in his own times. It is clear from Plato’s other writings that he had mixed motives: he wanted to entertain, improve and exalt his readers. A distant memory of the Minoan civilization was available, preserved for his use, as he said, by the seventh-century priests in the Nile delta. The wealth, orderliness and strangeness of the Minoans are sketched in for us. Atlantis has often been referred to as a Utopia, a fantastic extension of the ideal state Plato alluded to in the Republic, but it is really not that. It is the Athenians who are described in utopian terms. It is they who have relinquished private property, and have prolific fields and boundless pastures. It is Athens that is the excellent land with well-tempered seasons. Atticais the Utopia, not Atlantis, for all its marvels.

The second strand in Plato’s proto-history is hinted at in the words ‘all the island and over many other islands also’. Atlantis is an archipelago consisting of one large island and a group of smaller islands: the Aegean islands controlled by the Cretans in the sixteenth century BC. Such details of the destruction of Atlantis that Plato gives us speak of a geological cataclysm: earthquakes and subsidence taking significant parts of Atlantis below the waves. Small-scale gradual subsidences (and emergences) are common on all the Aegean islands – they tilt as a result of the ongoing collision between African and European plates – but something large-scale and sudden is meant. Red, white and black rocks are mentioned as building materials on Atlantis. Volcanic rocks like these exist on Santorini, an island that was the scene of a massive, destructive eruption in the bronze age, about a century before the Minoan civilization collapsed.

Atlantis - Third Part - Santorini eruptions

It was the eruptions of AD 19, 46–47 and 60 that created the island of Theia, ‘Divine’, now called Palea Kameini. The eruption of AD 60 was reported by Philostratus, together with the peculiar detail that the sea receded about one kilometre from the south coast of the island. This may have been associated with a tsunami, commonly produced by earthquakes focused on the seabed, and likely to occur during a submarine eruption.

In AD 726, Santorini experienced another major eruption. This was adjacent to Theia (Palea Kameini), produced a third island and threw ash as far as Macedonia and Anatolia.

In 1573 an eruption created the islet of Mikra Kameini to the east of Palea Kameini. In 1650 a series of earthquakes led up to a major submarine eruption off the north-east coast of Thera, forming a temporary island called Kouloumbos. Poisonous gases released during the eruption blinded or killed many Therans and their livestock.

In 1573 an eruption created the islet of Mikra Kameini to the east of Palea Kameini. In 1650 a series of earthquakes led up to a major submarine eruption off the north-east coast of Thera, forming a temporary island called Kouloumbos. Poisonous gases released during the eruption blinded or killed many Therans and their livestock.

Reconstruction of bronze age Thera

In the eighteenth century, Leychester reported that the new island had disappeared (eroded by wave action), forming a reef. According to other sources, the flames of the 1650 eruption were visible from Heraklion, and tsunamis swept among the Turkish ships beached on the island of Dia, close to the north coast of Crete.

For four years beginning in 1707 there were explosive eruptions of lava back in the caldera between Theia, now called Palea Kameini, and Mikra Kameini. The build up of lava created a new island called Nea Kameini: the eruptions of 1866–70 trebled its size. The King George I crater, formed at this time, is now 131 metres high. But for our story the main importance of this eruption sequence is that it attracted geologists and archaeologists to Santorini, where for the first time they recognized traces of a forgotten bronze age civilization.

There was a major explosion on Nea Kameini in August 1925 and the eruption that followed lasted nine months. 100 million cubic metres of lava poured out, joining Nea Kameini and Mikra Kameini and producing a lava dome. A further eruption in 1928 formed the Tholos and Nautilus craters. In 1939–41, the Nea Kameini craters were active again. In 1950 another explosion on the top of Nea Kameini led to the formation of the newest dome, Liatsikas, beside the King George I crater.

For four years beginning in 1707 there were explosive eruptions of lava back in the caldera between Theia, now called Palea Kameini, and Mikra Kameini. The build up of lava created a new island called Nea Kameini: the eruptions of 1866–70 trebled its size. The King George I crater, formed at this time, is now 131 metres high. But for our story the main importance of this eruption sequence is that it attracted geologists and archaeologists to Santorini, where for the first time they recognized traces of a forgotten bronze age civilization.

There was a major explosion on Nea Kameini in August 1925 and the eruption that followed lasted nine months. 100 million cubic metres of lava poured out, joining Nea Kameini and Mikra Kameini and producing a lava dome. A further eruption in 1928 formed the Tholos and Nautilus craters. In 1939–41, the Nea Kameini craters were active again. In 1950 another explosion on the top of Nea Kameini led to the formation of the newest dome, Liatsikas, beside the King George I crater.

For the last two millennia a long series of volcanic eruptions in the Santorini island group is well documented. Cone after cone has been added to the centre of the bay, the rim of which is the outer edge of a much bigger crater than any that has been active in the last 2,000 years. Unless the process is interrupted by another caldera eruption, the bay will eventually be refilled with lava and Santorini will be one island.

The geology shows that before the caldera eruption of 1520 BC Thera had already been disembowelled by more than one earlier eruption and the bronze age island had a substantial South Bay occupying the southernmost third of the modern caldera.

This south west basin may have been formed during a caldera eruption before 54,000 BC. Another caldera eruption near Cape Riva in 18,300 BC created the north west basin, so there may have been a bay, or at least low ground, between northern Therasia and Thera during the Minoan period.

The volcanic peaks visible on Santorini in the Minoan period had developed over a million years, from several vents within a preexisting island group of non-volcanic origin. Mesa Vouno and Profitis Elias, for instance, stood above the waves of the ancient Mediterranean much as they do now, long before the volcanic cone complex was built. Monolithos and Platinamos too stood up from this ancient sea, as peaked islets of schist and marble.

This south west basin may have been formed during a caldera eruption before 54,000 BC. Another caldera eruption near Cape Riva in 18,300 BC created the north west basin, so there may have been a bay, or at least low ground, between northern Therasia and Thera during the Minoan period.

The volcanic peaks visible on Santorini in the Minoan period had developed over a million years, from several vents within a preexisting island group of non-volcanic origin. Mesa Vouno and Profitis Elias, for instance, stood above the waves of the ancient Mediterranean much as they do now, long before the volcanic cone complex was built. Monolithos and Platinamos too stood up from this ancient sea, as peaked islets of schist and marble.

In the bronze age, Monolithos was still a separate islet, but Mesa Vouno and Profitis Elias were already engulfed in the volcano which made a single ‘Greater Thera’, an island shaped like a huge fish head with its mouth gaping towards the south west.

Reconstruction oft he bronze age Thera seen from the west

PART ONE OF THIS STORY @ Atlantis - Facts

Atlantis - Second Part - Santorini

On the southernmost edge of Thera, the main island of Santorini, the principal town of this civilization outside Crete was entombed and preserved by ashfall from the eruption. Was this the metropolis of Atlantis?

Figure 1: Location of the Thera (Santorini) island

It has been suggested that along the way, perhaps in transposing the story from Egyptian to Greek for Solon, there was a translation error, that Plato was really describing locations on two different islands, that the plain round the royal city was the Plain of Mesara on Crete, while the metropolis was on Thera.

Thera’s location, central in the Aegean and southernmost of the Cyclades, goes far towards explaining why it became prosperous in the bronze age. Within the small ring of islands – Thera, Therasia and Aspronisi – is a huge oval bay 10 kilometres across, the focus of the eruption that destroyed the bronze age civilization on Santorini. Where once hill country rose to volcanic peaks, the sea is now 400 metres deep. The steep walls of this caldera showing the layers of ash and lava of ancient volcanic eruptions give the bay a hostile coastline. Santorini’s main town, Phira, perches on the caldera rim, overlooking the bay. Today there are thirteen villages on Santorini and 6,000 people. Thirteen rural settlements are known from the bronze age too, but given the processes of destruction and burial it is unlikely that that we will ever see the complete pattern.

Figure 1: Location of the Thera (Santorini) island

It has been suggested that along the way, perhaps in transposing the story from Egyptian to Greek for Solon, there was a translation error, that Plato was really describing locations on two different islands, that the plain round the royal city was the Plain of Mesara on Crete, while the metropolis was on Thera.

Thera’s location, central in the Aegean and southernmost of the Cyclades, goes far towards explaining why it became prosperous in the bronze age. Within the small ring of islands – Thera, Therasia and Aspronisi – is a huge oval bay 10 kilometres across, the focus of the eruption that destroyed the bronze age civilization on Santorini. Where once hill country rose to volcanic peaks, the sea is now 400 metres deep. The steep walls of this caldera showing the layers of ash and lava of ancient volcanic eruptions give the bay a hostile coastline. Santorini’s main town, Phira, perches on the caldera rim, overlooking the bay. Today there are thirteen villages on Santorini and 6,000 people. Thirteen rural settlements are known from the bronze age too, but given the processes of destruction and burial it is unlikely that that we will ever see the complete pattern.

Ancient Santorini was probably more populous than today, with over 6,000 people in the city of Akrotiri alone.

Figure 2: Santorini or Thera, showing the location of the bronze age city at Akrotiri

Santorini suffers serious climatic problems, including perennial drought. Add earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and Santorini becomes a very hostile place.

The Aegean has always been dangerously earthquake-prone; here the African plate, invisible beneath the Mediterranean floor, drives slowly but inexorably under Europe. All Aegean islands are prone to earthquakes. The effect of the 1956 earthquake is still felt in Santorini. Forty-eight were killed and hundreds injured.

The Aegean has always been dangerously earthquake-prone; here the African plate, invisible beneath the Mediterranean floor, drives slowly but inexorably under Europe. All Aegean islands are prone to earthquakes. The effect of the 1956 earthquake is still felt in Santorini. Forty-eight were killed and hundreds injured.

The ensuing panic and disruption of everyday life caused many to leave, reinforcing a century-long trend to move to an easier life on the Greek mainland. Since 1956 hot gases and sulphurous emissions have steamed continuously from the craters and fissures in the middle of the bay. The forces that ravaged Santorini in 1956 will do so again as they did in antiquity, when they emptied it of its bronze age Atlanteans. In the centre of the caldera are the two newest islands in the Santorini group, Palea and Nea Kameini, the Santorini volcano rebuilding on its old foundations. Though no more than a few tens of metres high out of the water, they have been built to that height from the seabed, so they are already substantial volcanic peaks.

The first documented eruption was in 197 BC, when people from Rhodes saw an eruption that resulted in the creation of a small island: they called it Iera, ‘holy’, and dedicated an altar to Poseidon, the god of the Atlanteans.

For the volcano to have broken the sea surface in 197 BC it must have been building up to that level during a series of earlier eruptions that went unreported. Wave action later eroded the topof this volcano off, creating the Bankos Reef.

PART ONE OF THIS STORY @ Atlantis - Facts

For the volcano to have broken the sea surface in 197 BC it must have been building up to that level during a series of earlier eruptions that went unreported. Wave action later eroded the topof this volcano off, creating the Bankos Reef.

PART ONE OF THIS STORY @ Atlantis - Facts

ponedjeljak, 28. ožujka 2011.

The Creature Connection

The following article is written by NATALIE ANGIER

Bashert is a gentle, scone-colored, 60-pound poodle, a kind of Ginger Rogers chia pet, and she’s clearly convinced there is no human problem so big she can’t lick it. Lost your job, or bedridden for days? Lick. Feeling depressed, incompetent, in an existential malaise? Lick.

“She draws the whole family together,” said Pamela Fields, 52, a government specialist in United States-Japan relations. “Even when we hate each other, we all agree that we love the dog.” Her husband, Michael Richards, also 52 and a media lawyer, explained that the name Bashert comes from the Yiddish word for soul mate or destiny. “We didn’t choose her,” he said. “She chose us.” Their 12-year-old daughter, Alana, said, “When I go to camp, I miss the dog a lot more than I miss my parents,” and their 14-year-old son, Aaron, said, “Life was so boring before we got Bashert.”

Yet Bashert wasn’t always adored. The Washington Animal Rescue League had retrieved her from a notoriously abusive puppy mill — the pet industry’s equivalent of a factory farm — where she had spent years encaged as a breeder, a nonstop poodle-making machine. By the time of her adoption, the dog was weak, malnourished, diseased, and caninically illiterate. “She didn’t know how to be a dog,” said Ms. Fields. “We had to teach her how to run, to play, even to bark.”

Stories like Bashert’s encapsulate the complexity and capriciousness of our longstanding love affair with animals, now our best friends and soul mates, now our laboratory Play-Doh and featured on our dinner plates. We love animals, yet we euthanize five million abandoned cats and dogs each year. We lavish some $48 billion annually on our pets and another $2 billion on animal protection and conservation causes; but that faunophilic index pales like so much well-cooked pork against the $300 billion we spend on meat and hunting, and the tens of billions devoted to removing or eradicating animals we consider pest.

“We’re very particular about which animals we love, and even those we dote on are at our disposal and subject to all sorts of cruelty,” said Alexandra Horowitz, an assistant professor of psychology at Barnard College. “I’m not sure this is a love to brag about.”

Dr. Horowitz, the author of a best-selling book about dog cognition, “Inside of a Dog,” belongs to a community of researchers paying ever closer attention to the nature of the human-animal bond in all its fetching dissonance, a pursuit recently accorded the chimeric title of anthrozoology. Scientists see in our love for other animals, and our unslakable curiosity about animal lives, sensations, feelings and drives, keys to the most essential aspects of our humanity. They also view animal love as a textbook case of biology and culture operating in helical collusion. Animals abound in our earliest art, suggesting that a basic fascination with the bestial community may well be innate; the cave paintings at Lascaux, for example, are an ochred zooanalia of horses, stags, bison, felines, a woolly rhinoceros, a bird, a leaping cow — and only one puny man.

Yet how our animal urges express themselves is a strongly cultural and contingent affair. Many human groups have incorporated animals into their religious ceremonies, through practices like animal sacrifice or the donning of animal masks. Others have made extensive folkloric and metaphoric use of animals, with the cast of characters tuned to suit local reality and pedagogical need.

David Aftandilian, an anthropologist at Texas Christian University, writes in “What Are the Animals to Us?” that the bear is a fixture in the stories of circumpolar cultures “because it walks on two legs and eats many of the same foods that people do,” and through hibernation and re-emergence appears to die and be reborn. “Animals with transformative life cycles,” Dr. Aftandilian writes, “often earn starring roles in the human imagination.” So, too, do crossover creatures like bats — the furred in flight — and cats, animals that are largely nocturnal yet still a part of our daylight lives, and that are marathon sleepers able to keep at least one ear ever vigilantly cocked.

Researchers trace the roots of our animal love to our distinctly human capacity to infer the mental states of others, a talent that archaeological evidence suggests emerged anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. Not only did the new cognitive tool enable our ancestors to engage in increasingly sophisticated social exchanges with one another, it also allowed them to anticipate and manipulate the activities of other species: to figure out where a prey animal might be headed, or how to lure a salt-licking reindeer by impregnating a tree stump with the right sort of human waste.

Before long, humans were committing wholesale acts of anthropomorphism, attributing human characteristics and motives to anything with a face, a voice, a trajectory — bears, bats, thunderstorms, the moon.

James Serpell, president of the International Society for Anthrozoology, has proposed that the willingness to anthropomorphize was critical to the domestication of wild animals and forming bonds with them. We were particularly drawn to those species that seemed responsive to our Dr. Dolittle overtures.

Whereas wild animals like wolves will avert their eyes when spotted, dogs and cats readily return our gaze, and with an apparent emotiveness that stimulates the wistful narrative in our head. Dogs add to their soulful stare a distinctive mobility of facial musculature. “Their facial features are flexible, and they can raise their lips into a smile,” said Dr. Horowitz. “The animals we seem to love the most are the ones that make expressions at us.”

Dogs were among the first animals to be domesticated, roughly 10,000 years ago, in part for their remarkable responsiveness to such human cues as a pointed finger or a spoken command, and also for their willingness to work like dogs. They proved especially useful as hunting companions and were often buried along with their masters, right next to the spear set.

Yet the road to certification as man’s BFF has been long and pitted. Monotheism’s major religious texts have few kind words for dogs, and dogs have often been a menu item. The Aztecs bred a hairless dog just for eating, and according to Anthony L. Podberscek, an anthrozoologist at Cambridge University, street markets in South Korea sell dogs meant for meat right next to dogs meant as pets, with the latter distinguished by the cheery pink color of their cages.

As a rule, however, the elevation of an animal to pet status removes it entirely from the human food chain. Other telltale signs of petdom include bestowing a name on the animal and allowing it into the house. Pet ownership patterns have varied tremendously over time and across cultures and can resemble fads or infectious social memes.

Harold Herzog, a professor of psychology at Western Carolina University, describes in his book “Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat” how the rapid growth of the middle class in 19th-century France gave rise to the cartoonishly pampered Fifi. “By 1890, luxury and pet ownership went hand in hand,” he writes, and the wardrobe of a fashionable Parisian dog might include “boots, a dressing gown, a bathing suit, underwear and a raincoat.”

In this country, pet keeping didn’t get serious until after World War II. “People were moving to the suburbs, ‘Lassie’ was on television, and the common wisdom was pets were good for raising kids,” said Dr. Herzog in an interview. “If you wanted a normal childhood, you had to have a pet.”

Pet ownership has climbed steadily ever since, and today about two-thirds of American households include at least one pet.

People are passionate about their companion animals: 70 percent of pet owners say they sometimes sleep with their pets; 65 percent buy Christmas gifts for their pets; 23 percent cook special meals for their pets; and 40 percent of married women with pets say they get more emotional support from their pets than from their husbands. People may even be willing to die for their pets. “In studies done on why people refused to evacuate New Orleans during Katri

Looters strip Latin America of archaeological heritage

Etched into the surviving art of the Moche, one of South America's most ancient and mysterious civilisations, is a fearsome creature dubbed the Decapitator. Also known as Ai Apaec, the octopus-type figure holds a knife in one hand and a severed head in the other in a graphic rendition of the human sacrifices the Moche practiced in northern Peru 1,500 years ago.

"They come at night to explore the ruins and dig the holes," said Cuba Cruz de Metro, 58, a shopkeeper in the farming village of Galindo. "They don't know the history, they're just looking for bodies and for tombs. They're just looking for things to sell."

A looting epidemic in Peru and other Latin American countries, notably Guatemala, has sounded alarm bells about the region's vanishing heritage.

The issue is to come under renewed scrutiny in the run-up to July's 100th anniversary of the rediscovery of Machu Picchu, the Inca citadel in southern Peru, by US historian Hiram Bingham. He gave many artefacts to Yale university, prompting an acrimonious row with Peru's government which ended only this year when both sides agreed to establish a joint exhibition centre.A recent report, Saving our Vanishing Heritage, by the Global Heritage Fund in San Francisco, identified nearly 200 "at risk" sites in developing nations, with South and Central America prominent.

Mirador, the cradle of Mayan civilisation in Guatemala, was being devastated, it said. "The entire Peten region has been sacked in the past 20 years and every year hundreds of archaeological sites are being destroyed by organised looting crews seeking Maya antiquities for sale on the international market."Northern Peru, home to the Moche civilisation which flourished from AD100-800, had been reduced to a "lunar landscape" by looter trenches across hundreds of miles. "An estimated 100,000 tombs – over half the country's known sites – have been looted," the report said.

The sight breaks the heart of archaeologists and historians piecing together the story of a society which built canals and monumental pyramid-type structures, called huacas, and made intricate ceramics and jewellery.

The Moche, who pre-dated the Incas by 1,000 years, also painted murals and friezes depicting warfare, ritual beheading, blood drinking and deities such as the Decapitator, who has bulging eyes and sharp teeth. Analysis of human remains confirmed that throat-cutting was all too real but, in the absence of written records, archaeology must shed light on what happened.

Most huaqueros are farmers supplementing meagre incomes. Montes de Oca, one of three police officers tasked with environmental protection in a region of a million people, said he was overwhelmed. "I've been doing this for 28 years. There are three of us and one truck. It's insufficient but we do everything possible."

Ten miles away Huaca del Sol, one of the largest pyramids in pre-Columbus America, is an eroded, plundered shell. Here the culprits were not impoverished farmers but Spanish colonial authorities who authorised companies to mine for treasure, said Ricardo Gamarra, director of a 20-year-old conservation project.

"They diverted the river to wash away two-thirds of the huaca and reveal its insides," he said. "They mined through the walls and caused it to collapse in various places. It's impossible to guess how much was taken because we don't know how much was there."

Donations from businesses and foundations have helped Gamarra's team protect what is left, drawing 120,000 visitors each year, but of 250 other sites in the region just five have been protected. "In the mountains it's the same. It is full with archaeological sites, almost all of them have been destroyed," said Gamarra.

There has been good news from Chotuna, also in northern Peru, where archaeologists found frescoes in a 1,100-year-old temple of the Lambayeque civilisation, which flourished around the same time as the Incas.

Jeff Morgan, executive director of the Global Heritage Fund, urged Peru to funnel tourists away from Machu Picchu, overrun by two million visitors a year, to lesser known sites which could then earn revenue to protect their heritage.

The government should resist the temptation to pocket the money. "One of the biggest problems is the disconnect between local communities and management of the sites. We think locals should get at least 30% of revenues." Only then, said Morgan, would cultural treasures fom the Moche and other civilisations be saved.

Humans arrived in North America 2,500 years earlier than thought

Humans first arrived in North America more than 2,500 years earlier than previously thought, according to an analysis of ancient stone tools found in Texas. And the people who left them appear to have developed a portable toolkit used for killing and preparing meat.

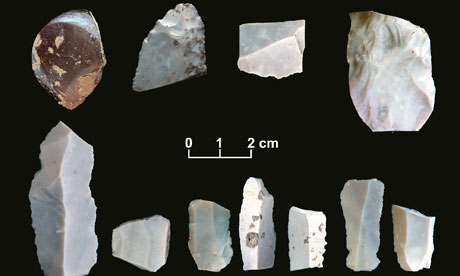

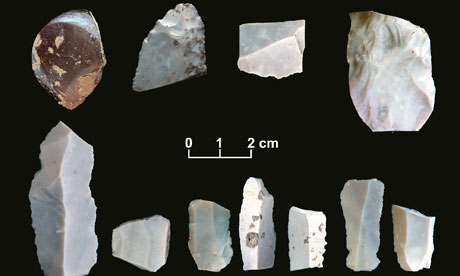

Researchers found a haul of thousands of artefacts near the state capital, Austin, some of which were identified as blades and other tools. The material was buried in sediments that are between 13,200 and 15,500 years old.

Stone tools were found in 15,500-year-old sediment, pushing back the oldest evidence of human occupation in North America. Photograph: Michael R Waters/Science

There are problems with this story, however. Clovis-like tools, known for their distinctive fluted points, have never been found in northeastern Asia. And stone tools found in Alaska are too young (and too different) to be associated with Clovis.

"This discovery challenges us to rethink the early colonisation of the Americas," said Waters. "There's no doubt these tools and weapons are human-made and they date to about 15,500 years ago, making them the oldest artefacts found both in Texas and North America."

He added: "This makes the Friedkin site the oldest credible archaeological site in Texas and North America. The site is important to the debate about the timing of the colonisation of the Americas and the origins of Clovis."

The researchers think that the tools were made small so they could be used in a mobile toolkit, easily packed up and moved to a new location. Though the tools are noticeably different from the Clovis technology, Waters thinks that they could be related. "This discovery provides ample time for Clovis to develop. People [from the Buttermilk Creek Complex] could have experimented with stone and invented the weapons and tools that we now recognise as Clovis ... In short, it is now time to abandon once and for all the 'Clovis First' model and develop a new model for the peopling of the Americas."

Researchers found a haul of thousands of artefacts near the state capital, Austin, some of which were identified as blades and other tools. The material was buried in sediments that are between 13,200 and 15,500 years old.

Until now, the oldest evidence for human occupation in North America has come from the Clovis site in New Mexico. Scientists think that these people came to North America around 13,000 years ago by crossing the Bering Land Bridge from northeastern Asia. From there, they are thought to have spread across the northern and southern American continents.

Michael Waters from Texas A&M University led a team of researchers to study the Debra L. Friedkin site in Texas, about 40 miles northwest of Austin. Buried underneath the layer of rock that has been associated with the time period for the Clovis humans, his team found more than 15,000 objects that indicated the presence of an older civilisation.

He added: "This makes the Friedkin site the oldest credible archaeological site in Texas and North America. The site is important to the debate about the timing of the colonisation of the Americas and the origins of Clovis."

The analysis of the artefacts found at the site, which researchers have called the Buttermilk Creek Complex, is published in the latest issue of Science. "Most of these are chipping debris from the making and re-sharpening of tools, but over 50 are tools," said Waters. "There are bifacial artefacts that tell us they were making projectile points and knives at the site. There are expediently made tools and blades that were used for cutting and scraping."

The stone tools at Buttermilk Creek were dated using an optical technique called luminescence dating, which uses changes in luminescence levels in quartz or feldspar as a clock to pinpoint the time that objects were buried in sediment. "We found Buttermilk Creek to be about 15,500 years ago – a few thousand years before Clovis," said Steven Forman of the University of Illinois, who is a co-author on the paper. He added that it was the first identification of pre-Clovis stone tool technology in North America.